When asked how many hours they work, people tend to give the hours spent in paid employment. But paid work isn’t the only work people do. If ‘work’ only meant paid work then hunter gatherers and slaves must have spent their lives in idle leisure. That is obviously absurd.

So what exactly do we mean by ‘work’?

Physicists define work as the energy transferred when moving an object. More generally, work is effort directed towards a particular goal. Hence we have housework, homework, woodwork etc. In modern usage, work usually refers to time dedicated to activities for financial payment.

The definition matters, because conflating work with paid employment underestimates the total amount of work that is done. Attempts have been made to incorporate unpaid work into GDP measures, but without great adoption. Still, we should be mindful that we work a lot more than is captured in hours of paid employment, particularly as these are used as evidence of improving living standards. If it turns out we work more than hunter gatherers worked prior to civilisation and technology, it wouldn’t say much for modern economies.

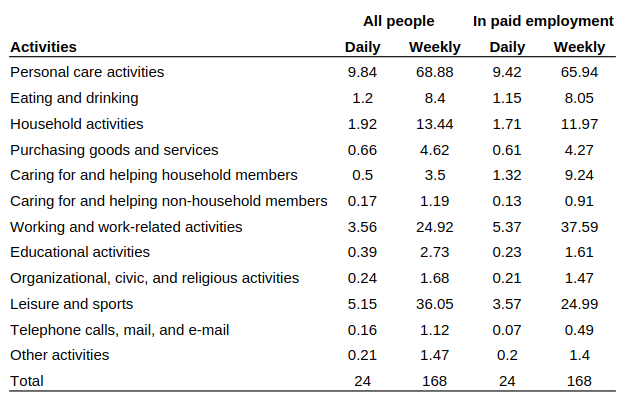

The Bureau of Labor Statistics American Time Use Survey 2023 asked Americans how many hours a day they spent on various activities.

The average hours spent in paid employment and related activities, were 3.56 for all people and 5.37 for employed people. These are average figures spread over seven days, which work out at around 25 hours per week for all people and 37.5 hours for employed people.

This leaves quite a few hours left over. So what else are people doing with their time and how much of it should really be considered work?

The breakdown looks like this:

Personal care activities include sleeping, toilet breaks, grooming, and sex apparently. You could certainly make a case that grooming and even sex count as working. But this seems contentious and no further time breakdown is given so for simplicity’s sake I will omit all personal care activities. Similarly for eating and drinking; although these are things necessary for survival they do not count as work.

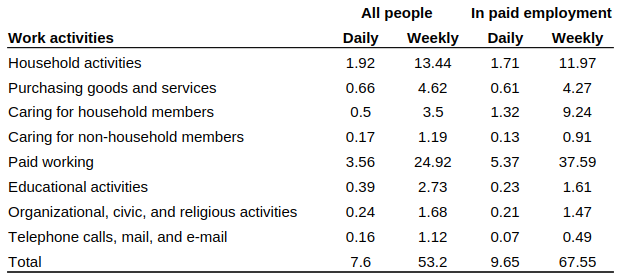

Household activities, according to the text, are housework, hence clearly work.

Whether purchasing goods and services count as work is debatable. Some people shop for pleasure. I find it tedious and stressful and would much rather be doing other things. This should count as work as it takes effort, is essential for survival, and we have little choice but to undertake it.

Caring for other people seems to me obviously work. Educational activities can be pleasurable but should also count as work. Organizational, civic and religious activities aren’t well defined but to me fall into the work category.

Leisure is obviously not work. Sports I consider non-work. Exercise should probably count as work but the amount of it that Americans do is so small it makes little difference to the total.

Telephone calls, mail and email seem to me obviously work.

The study does not record how much time is spent on social media and other internet browsing. It seems likely these are included in leisure activities or socialising and communicating.

This gives a revised figure of 7.6 hours of work per day for all people, 9.65 for employed people. These amount to 53.2 hours and roughly 67.5 hours per week respectively.

How accurate are the data? They record 43.9% of respondents as being in work, much lower than the figures given in other statistics (FRED, Statista) of around 60%. The reasons given for the discrepancy are that the inclusion age started at 15 rather than 16 and that the survey was conducted on all days rather than just weekdays. Another likely reason is that the survey sampled households by telephone when many would be at work. This, combined with the exclusion of grooming and exercise, very likely means the average working hours are an underestimate.

Estimates for the number of hours worked per week among hunter gatherers are in the range of 15 to 45. Even the higher end of these estimates is substantially lower than the working hours of an average modern-day American.

Modern work is physically less demanding but has less autonomy and more stress. Moreover, the lack of physical effort is causing severe health problems. We should be spending much more time on exercise to compensate, which would increase our work time further. Americans only spend 0.21 hours per day on exercise while hunter gatherers would have been physically active for much of the day.

Only 29.2% of respondents engaged in socialising and communicating each day while only 21.1% participated in sports and exercise (this includes spectator sports). This compares to compared to 73.7% who watched television each day. The average time per day spent on socialising was 34 minutes compared to 2.67 hours watching television.

It’s little wonder many people suffer mental health problems and burnout. We are simply working more, while socialising and exercising less, than our minds and bodies evolved for.

There is also an underlying philosophical issue. Activity only counts as work when some other person or organisation is willing to exchange money for it. It’s essentially a form of servitude. Meanwhile, the work we do for ourselves is considered valueless. This makes autonomous living seem a selfish indulgence; a primitive, animalistic way of life.

Concurrently, work is deprived of pleasure; it is a burden to be endured, a ritual of suffering to placate society. Not only is work unpleasant. It should be unpleasant, and if it isn’t, it’s not considered real work. Hence the scorn for creative professions.

And of course, most modern work is unpleasant. In contrast, many traditional working activities such as hunting, fishing, weaving and foraging, are today undertaken purely for pleasure; some people in fact pay considerable sums to perform them. But people don’t work in accounts for fun, or telemarketing. No one (at least no one sane) does B2B sales for a hobby. A few may tinker with electronics and computer programs, but generally on ‘fun’ projects the market has no interest in. If AI automates away our current paid activities, it will be interesting to see how many continue to be practiced for pleasure alone.

Modern life with all its conveniences mighy be comfortable, but not necessarily fulfilling. Previous generations may have worked harder, but for fewer hours, and with a stronger distinction between work and relaxation. We exist in a perpetual netherworld of sort-of-work, fixed to our screens, simultaneously bored, stressed and dissatisfied. Things will likely change as AI takes over. Whether or not for the better remains to be seen.